Office clerk Stefan Kiszko spent 17 years in prison for the murder of schoolgirl Lesley Molseed in Rochdale in northwest England in 1975. Though he had confessed his guilt to the police at the time, evidence later proved he was innocent.

I grew up in Rochdale and remember reading about the case in the local newspaper as a teenager. I always wondered why an innocent person would confess to a crime they hadn’t committed.

In fact, most people believe they wouldn’t confess to a crime they hadn’t committed. After all, it is counter-intuitive that an innocent person would do this. False confessions are usually retracted, yet once given they are difficult to discard. Jurors are usually not even swayed when it turns out the suspect was coerced during the interrogation.

But innocent people do confess. According to research from the US, over 25% of people later exonerated by DNA evidence made a false confession. So, what makes an innocent person admit to a serious crime?

Extracting confessions

In the US and Canada, investigators typically use a type of interrogation known as the Reid Technique – named after former Chicago police officer John Reid. Prior to an interrogation, suspects are observed for signs of lying and truth-telling. If the interviewer thinks they are lying, they interrogate them in a way that presumes guilt – interrupting any denials and refusing to believe their account.

As part of the technique, interviewers may also lie about evidence, for example telling the suspect they have failed a lie detector test or that their DNA was found at the scene. If a suspect thinks the jury will find them guilty, confessing may rationally seem the best thing to do.

The Reid technique can even convince some innocent suspects that they are guilty. Suspects will sometimes reenact a crime they did not commit. In such cases, their detailed knowledge of the crime is damning, yet may have been fed to them during interrogation.

In the UK, these coercive techniques are not permitted. The UK is a leader in ethical interviewing, thanks to a technique introduced in the early 1990s known as the investigative interview. It focuses on gathering information rather than obtaining a confession, and has significantly improved interview practice.

Suspects are treated more fairly and the evidence that is produced is higher quality. It is also mandatory to make an audio/video recording of the interview, which acts as an extra safeguard. Scotland, meanwhile, requires corroboration, meaning there must be independent evidence supporting the confession.

Vulnerabilities

Some people are more at risk of being influenced by manipulative interview techniques than others – those who are more suggestible or who aim to please, for instance. Such people are more likely to agree with an officer’s account of the event, or change answers based on feedback. Low self confidence and even sleep deprivation can further increase the likelihood of a false confession.

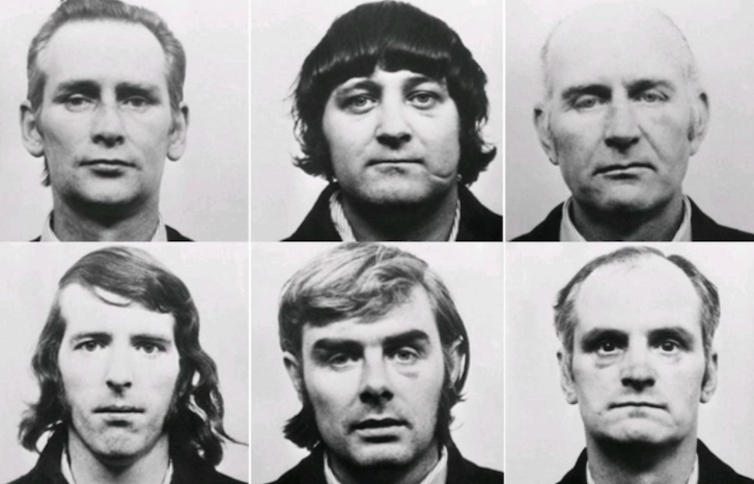

The UK case of the Birmingham Six is a classic example of differences in people’s susceptibility to confessing under pressure. It concerned the 1975 bombing of two Birmingham pubs, killing 21 and injuring almost 200 others. The attack was attributed to the provisional IRA, but the six innocent Irish Catholic immigrants who were handed life sentences were released 16 years later after they were deemed to have been wrongfully convicted. The men were severely abused in police custody, and personality tests later showed that the four who confessed were more suggestible and compliant than the two that didn’t.

Wikimedia

Certain types of question can also lead to inaccurate accounts. Leading questions can alter a person’s memory of an event. They might narrow response options or presume certain information to be true. In one study, for example, asking people whether they had seen “the” broken headlight rather than “a” broken headlight doubled the number who falsely remembered seeing it.

Fans of TV series Making a Murderer will recognize such questions from the interviews of Brendan Dassey. Despite being a minor with a below-average IQ, he was interviewed without a lawyer, and many believe it was a coercive interrogation. He confessed to playing a part in the murder of Teresa Halbach and is currently serving a life sentence.

Children and vulnerable adults are particularly susceptible to false confessions. They may have less understanding of consequences, or may focus on the short-term reward of finishing the interview. Despite having a mental age of around 12 years and a low IQ, for example, Stefan Kiszko was interviewed in Rochdale without a solicitor. At the trial, he retracted his confession and claimed the police had bullied him into his statement. He said he had believed that the evidence would absolve him, yet no such evidence reached the jury.

Sadly, Kiszko died shortly after his release. His mother, who had fought tirelessly to clear his name, died a year later. He never received the compensation he was due. The real culprit, Ronald Castree, was only identified in 2007.

There will always be guilty people who deny their crimes, but we must remember the presumption of innocence until guilt is proven. There is a high risk of false confessions in some countries, and even in the UK, they are not eliminated entirely. To prevent further miscarriages of justice, suspects’ psychological vulnerabilities must be recognized and appropriate procedures put in place.

Researchers and legal professionals need to increase public awareness so that jurors understand the social and psychological risk factors – to this end, I’m doing a show on this subject at this year’s Edinburgh Fringe. Jurors need to understand that it’s wrong to assume that confessions are always true, before it destroys the lives of any more people standing in the dock.

Faye Skelton, Lecturer in Cognitive Psychology, Edinburgh Napier University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.