My ideas about animal behavior were turned upside down in 2002 when I watched Betty, a New Caledonian crow, fashion a hook from a piece of wire and use it to pull a small container with meat from a tube.

Betty’s behavior captivated scientists because it seemed so creative: there was no obvious solution to the problem yet Betty had found a way. How could this crow be thinking, given it was separated from humans by 620 million years of independent evolution?

Our latest research, published today, helps us answer this question. It provides conclusive evidence that, like a chess player thinking several moves ahead, New Caledonia crows can plan out a sequence of three behaviors while using tools in order to solve a problem.

Clever birds

Over the past 20 years, New Caledonian crows have produced a variety of behaviours that have suggested they might be highly intelligent. But creating conclusive evidence for what is actually going through the mind of an animal is tricky.

Read more:

Bird-brained and brilliant: Australia’s avians are smarter than you think

In past work, we have given crows problems that require longer and longer sequences of behavior. But to really understand if New Caledonian crows can plan, we needed to distinguish between online planning and preplanning.

Online planning involves making a plan on a moment-to-moment basis. It can be thought of as essentially planning on the fly; you make one move, assess the effects, and then plan the next. Preplanning is true planning. You plan a sequence of steps ahead, such as when thinking two or three moves ahead in chess, and then carry out those steps.

Seventeen years on from Betty’s hook bending, thanks to a training breakthrough by three of our team (Romana Gruber, Martina Schiestl and Markus Boeckle), we were finally able to design an experiment to test the birds’ planning skills.

Solving complex problems

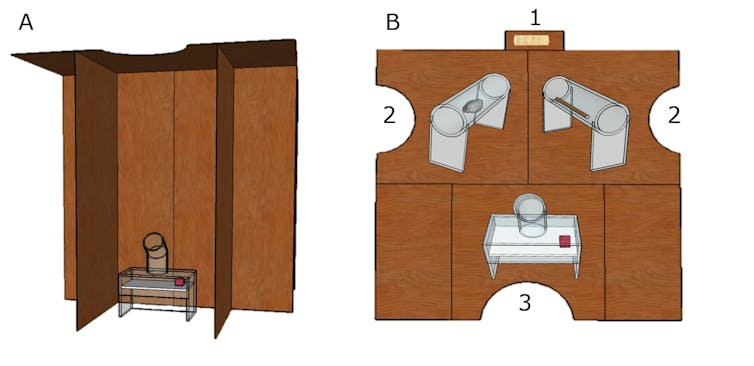

We presented the crows with a difficult problem. Crows had to use a short stick to pull a stone from a tube, and then use this stone to release a platform to get meat, while ignoring another tube that contained a long stick. The catch was that each stage of the problem was out-of-sight of the others, hidden by a wooden shield that prevented the crows from seeing more than one part of the problem at a time. To make things harder, we swapped the position of the two tubes randomly between trials, so crows had to remember where they had last seen the correct tool.

Alex Taylor, CC BY-ND

This meant that as the crows approached the problem, they had to mentally represent where the long stick, stone and meat were, and then use these representations to form a plan of what to do once they had picked up the short stick. Solving the problem on a moment-to-moment basis (i.e. by online planning) would lead them to make mistakes.

Highly surprisingly, some of the crows we presented with this problem did exceptionally well. One individual, Saturn, actually never made a mistake on this task.

Evolution of planning

These results show New Caledonian crows can pre-plan three behaviors into the future. While they suggest that Betty planned out her wire bending behaviors, the implications of these results go far beyond explaining her behavior.

New Caledonian crows have so far sparked such interest because they are a highly useful model species to understand the evolution of tool use. Our results mean we can now use these birds to understand something even more fundamental: the evolution of planning itself.

Planning is one of the most powerful cognitive abilities humans have. When combined with our tool use it has allowed us to reach the heights of civilization we currently enjoy. This combination is therefore at the heart of what is means to be human.

Now we know another species, a tool-using crow, living on an island in the Pacific, can also combine these abilities. Understanding their story, of how they came to be able to possess these skills, will teach us much about our own story, about why we evolved to think the way we do today.

Alex Taylor, Senior Lecturer, University of Auckland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.