In 2007, Haitian-American artist Moliere Dimanche was sentenced to 10 years in Florida state prisons, where he ended up serving eight-and-a-half years.

While imprisoned, he made art – a series of pencil drawings on the back of stray sheets of paper – to document the brutality of his time spent behind bars, much of it in isolation.

In 2017, I was introduced to Dimanche, one of the dozens of currently and formerly incarcerated people I have interviewed over the past several years for my forthcoming book on visual art in the era of mass incarceration.

Often using state-issued material or contraband, imprisoned artists use a myriad of genres and styles to create political collages, portraits of other imprisoned people and mixed-media works that comment on abuse, racism and the exploitation of prison labor.

In Dimanche’s story, I see the stories of thousands of others in U.S. prisons who are using art and creativity to shine a light on their experiences and advocate for systemic change.

A malignant system

Florida prisons, in particular, have become notorious for their pervasive culture of neglect and abuse.

In 2016, investigative reporter Eyal Press wrote about the torture and routine abuse that took place in the mental health units of Florida’s prisons.

Central to Press’ account was the case of Darren Rainey, an incarcerated man with a history of schizophrenia who was scalded to death when prison officers forced him into a shower of boiling hot water.

According to The Miami Herald, at least 145 people have died in state penal facilities so in 2018, making Florida’s prisons among the deadliest in the country.

In response, many inside have resisted or continue to resist the inhumane treatment and prison conditions. Earlier in 2018, prison laborers in Florida organized a strike to protest unpaid labor and brutal working conditions. (Many of the participants were punished with solitary confinement.)

In August, incarcerated people in Florida joined others across the country in a nationwide prison strike. Their demands include being paid prevailing state wages for their labor, reforms that would allow prisoners to file grievances when their rights are violated, and a reinstatement of Pell grants in all U.S. states and territories.

While these strikes can certainly bring attention to dire prison conditions, the stories of incarcerated people can also emerge in creative and clandestine ways – in drawings, photographs, paintings, letters and poetry.

Incarcerated activists like Kevin “Rashid” Johnson – whose Guardian essay denouncing prison labor as “modern slavery” went viral in August – also use art to communicate with the public.

Because prisons are institutions of constant surveillance and censorship, art can serve as a crucial conduit for self-expression and as a tool for survival – a way to earn money, document prison conditions and stay connected with the outside world.

Drawing to survive

After Moliere Dimanche was sentenced, his family was unable to financially support him. From the costs of phone calls to commissary items to the expenses of visits to see imprisoned relatives, prisons can be a financial drain for families already struggling to get by.

Dimanche soon realized that he could use art as currency for toiletries, clothing, cigarettes, writing utensils and coffee. Other incarcerated men – and even some prison staff – commissioned him to make portraits, drawings and greeting cards that they would then give to their loved ones. He also designed tattoos and fashioned a tattoo gun and ink from prison supplies.

Dimanche ultimately created a series of fantastical, highly symbolic, allegorical drawings during his time in solitary confinement. They are bold, cartoonish representations. Filled with dark humor, they provide a sustained lens into the abuses inside Florida’s prison system.

While art gave him a way to provide for his basic needs and acted as an outlet for creative expression, Dimanche also became an expert of the state’s penal system and how it stifles the rights of the imprisoned. Early into his sentencing, he began to study law and to advocate for himself and others.

He became a writ writer – a jailhouse lawyer – filing grievances and writing briefs on behalf of fellow prisoners and himself.

But he believes his legal advocacy only subjected him to more punishment and surveillance. He was held in solitary confinement for much of his sentence.

Even in isolation, he continued his writ writing and making art.

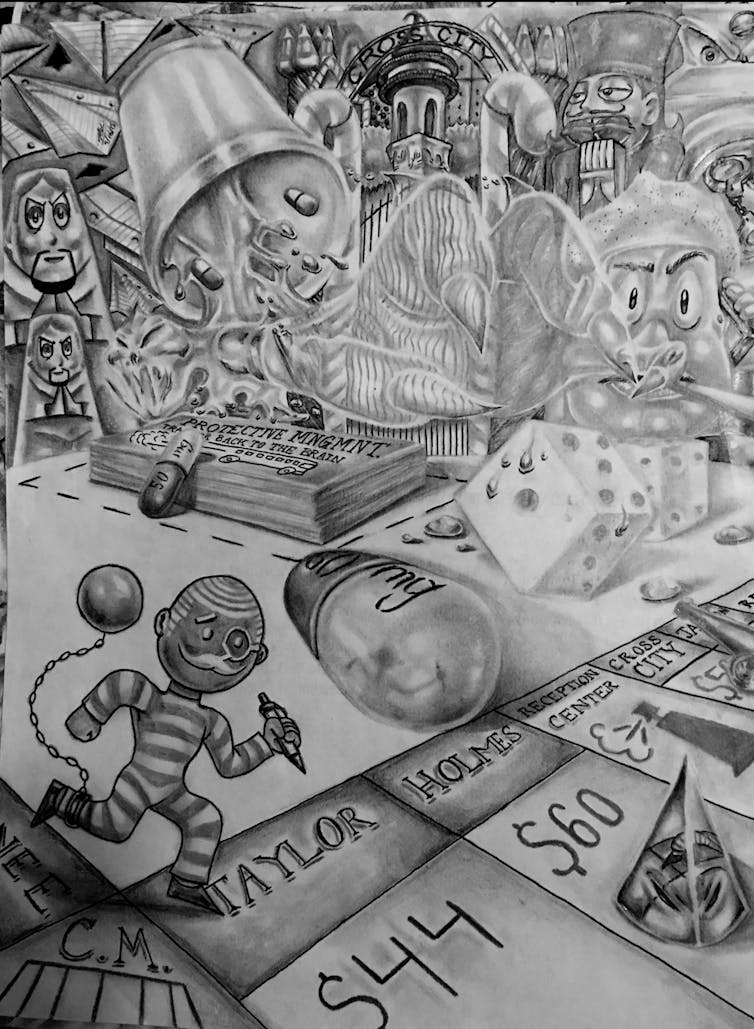

In a piece called “Pills and Potions,” Dimanche depicts himself as the Monopoly Man, and converted the Monopoly board into the Florida Department of Corrections, with each property representing a different prison.

Moliere Dimanche, Author provided

“I had been bounced around so much for writing grievances,” he explained,

“I just depicted myself as the Monopoly man running around the board, bouncing around from prison to prison.”

“I had to find a way to laugh about some of this stuff.”

There’s nothing funny about some of the brutal forms of punishment depicted in many of his pieces.

There’s what Dimanche calls “the strip” – a punishment in which guards “take your linen, they take your mattress, and they take your clothing, and they put you in a cell for 72 hour restriction and you don’t have anything in there … and it’s absolutely freezing in that cell and you have stay in it without clothing or anything the whole time.”

According to Dimanche, “saving a life” involves a corrections officers shackling a prisoner to supposedly take him to a medical appointment. But once he’s out of the cell and out of sight, they slam the prisoner’s head against a wall.

Dimanche also documents a common abuse practice in Florida where officers gas people confined to their cells. These practices have led to reported deaths. Dimanche calls one form of gassing “Black Jesus”: Guards lock someone an isolation cell and gas them through the porthole. The gas, he explains, “comes in a big black can and it’s known to make people scream for Jesus.”

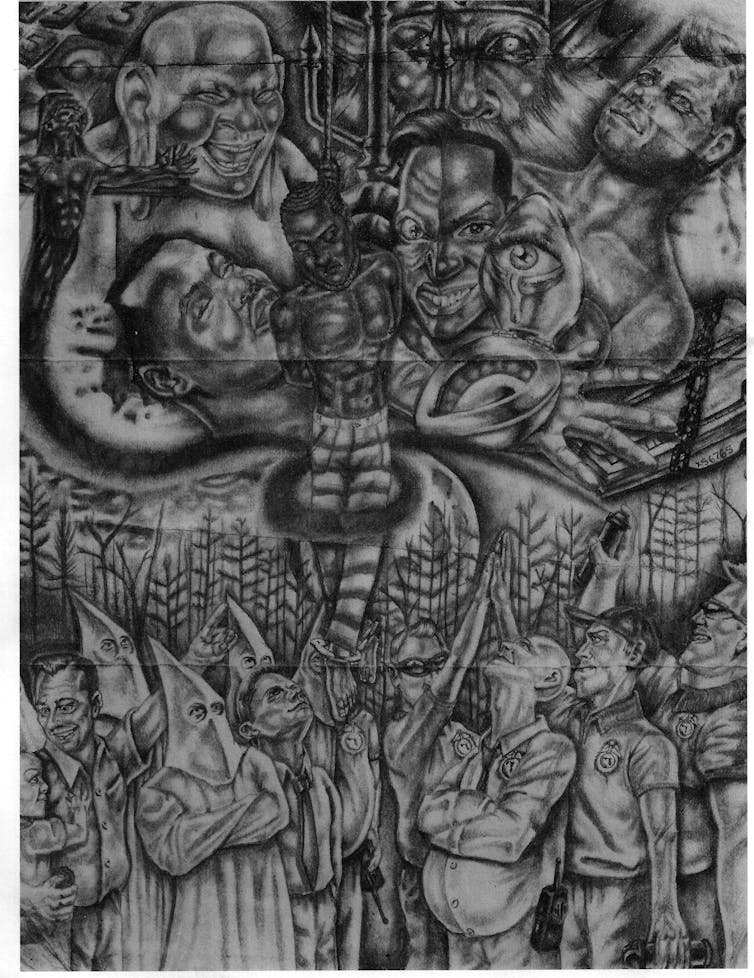

Dimanche titled one of his pieces after this punishment by gassing, and depicts a guard gleefully spraying a hanging Dimanche.

Moliere Dimanche, Author provided

“Black Jesus” also highlights the racism of Florida’s prisons, where an ACLU study found black people are subjected to more abuse. In 2017, two former Florida prison guards who were Klan members were convicted of plotting to murder an imprisoned black man.

Dimanche witnessed this racism firsthand. “I was in a couple of institutions where it was revealed where a lot of the correctional officers were Klansmen,” he said.

In “Black Jesus,” he portrays a man who is half dressed as an officer and half dressed in a Klan robe to symbolize, according to Dimanche, how each group uses force to “reinforce old Jim Crow ideas.”

A connection is made – and a bond forms

Eventually, another prisoner in solitary confinement put him in touch with Wendy Tatter, an artist living in St. Augustine, Florida. Tatter’s son had also spent time in Florida prisons, and Dimanche wrote to her asking if she’d be interested in seeing his art.

Tatter recalled to me Dimanche’s first letter – sent in September 2013 and written in a tiny font, so he could cram as much information as he could on the few sheets of paper available to him.

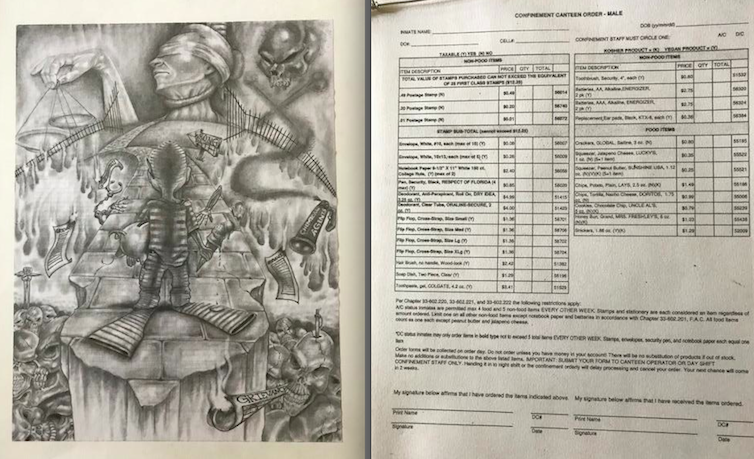

She agreed to see his work, and he started mailing her “these gorgeous original pencil drawings.”

She told me that each was made with a broken pencil and no eraser. They arrived “on just random pieces of paper that he managed to find” – on the backs of order sheets, Manila folders and old letters.

Moliere Dimanche, Author provided

The two wrote back and forth for three years until his release in 2016. Since then, he and Tatter have worked together to exhibit his work.

On Sept. 9 – the day that the national prison strike ends – Moliere and Tatter will host a program on mass incarceration and prison reform at the Corazon Cinema and Café in St. Augustine, Florida.

“Even though there’s a lot of talk about prison reform now, it’s bigger than sentencing guidelines,” Dimanche told me. “We have to address the physical abuse in prisons.”

Lack of transparency and access to prisons and detention centers makes this work extremely difficult.

Dimanche hopes that his art will open some eyes, and eventually end the American tradition of locking up, neglecting, exploiting and abusing millions in prisons across the country.

Nicole R. Fleetwood, Associate Professor of American Studies, Rutgers University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.