Rewilding is often thought of as a fantastical vision of the future. One day we might share the landscape with wolves and bears, but in the present day, it seems unlikely. For many people in Europe though, that’s exactly what they’ve been doing for at least the past decade.

Rewilding means bringing back the species and habitats which have disappeared from a region. Initially, conservationists imagined creating vast nature reserves which could be connected by “wildlife corridors” of forest, so that carnivores such as lynx could be reintroduced and thrive in a landscape that’s been heavily altered by humans.

Read Also: The Mystery of the Blood Falls of Antarctica Solved

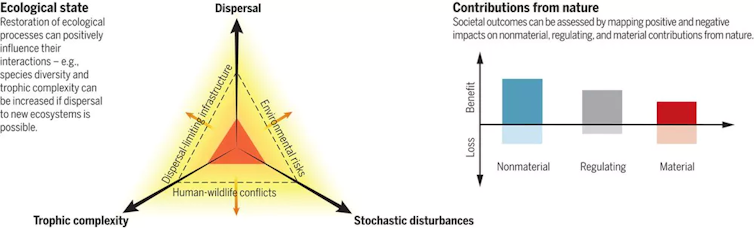

But that idea is changing. The current emphasis goes beyond just restoring habitats for reintroduced species and considers ecosystems as a whole, and how they can be helped to recover. Better yet, much of this involves little human effort and could have positive consequences for society and ecosystems.

Author provided

From agricultural land to forest

The cheapest and most effective way to rewild a landscape is to eliminate or reduce as much as possible the causes that have contributed to degrade it. For the last 12,000 years in Europe, these causes have largely involved agriculture and grazing livestock which have destroyed natural vegetation, especially forests, grasslands and wetlands, and replaced them with cropland and pastures.

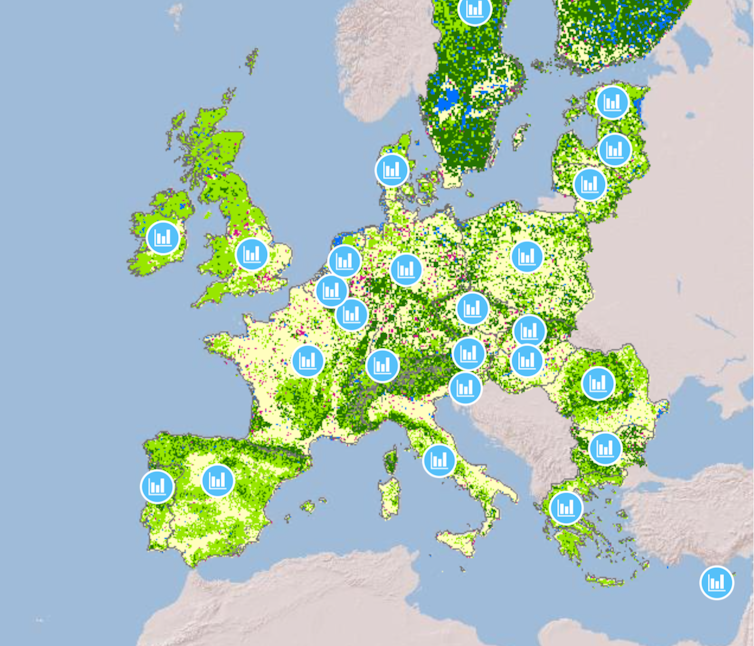

But as people have migrated from rural areas to cities, large areas of farmland – especially isolated patches in remote areas – have returned to nature. This has been happening in Europe since the second half of the 20th century.

Department of Geoinformation Science and Remote Sensing, Wageningen University, Netherlands.

Department of Geoinformation Science and Remote Sensing, Wageningen University, Netherlands.

As crops and pastures are abandoned, shrubland and forests naturally regenerate. Despite 40% of the world’s land being cultivated or grazed permanently by domestic herbivores, there has been a big increase in the area occupied by forests in recent decades, explained mainly by these habitats naturally regenerating as humans have left.

Forests returned at a rate of 2.2m hectares per year between 2010-2015 alone. Spain, for example, has tripled its forest area since 1900 – increasing from 8% to 25% of its territory. The country gained 96,000 hectares of forest every year from 2000-2015.

All this new habitat has been recolonized by wildlife. Populations of large carnivores such as the brown bear, the wolf, the Eurasian lynx and the wolverine have all increased in Europe. Populations of large and medium-sized herbivores, such as the red deer, the wild boar, the roe deer and the Iberian ibex, have also increased. Other species, such as the Iberian lynx and the European bison, have been reintroduced on purpose.

Restore as much as possible of landscape

The same strategies cannot be generalized everywhere, nor should the aim always be to recover pristine ecosystems, which is often simply impossible in today’s world.

The goal in most cases should be to improve the ecological condition of the landscape as much as possible and ensure they can serve multiple functions for people and wildlife. Ecological restoration should be flexible and pragmatic without losing awareness of what the natural ecosystem originally looked like, so as to regain the highest possible levels of biodiversity.

Author provided

In Europe, around 30% of the land is cultivated for crops and another 15% is covered by pastures or heath and moorland. Around 10% of the territory is made up of towns, cities and roads. More wilderness could be encouraged in all these environments, which could allow agriculture and livestock production or residential areas and industry to coexist with higher levels of biodiversity.

Large parts of Europe have been passively rewilding for decades as people have moved out of rural areas. Reintroducing species more widely can only be done with the approval of the different people likely to be affected. Due to the low densities of people in the remote fringes of Europe’s rural areas, they remain the best options for places to reintroduce wild herbivores and carnivores which would restore natural processes thanks to their key role in food webs.

José M. Rey Benayas, Catedrático de Ecología, Universidad de Alcalá

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.