In an ideal world, people would look at issues with a clear focus only on the facts. But in the real world, we know that doesn’t happen often.

People often look at issues through the prism of their own particular political identity – and have probably always done so.

However, in an environment of fake news, filter bubbles and echo chambers, it seems harder than ever to get people to agree about simple facts.

In research published today in Environmental Communication, my colleague Matthew Nurse and I report that even some of the smartest among us will simply refuse to acknowledge facts about climate change when we don’t like them.

Read more:

Why old-school climate denial has had its day

Skin cream versus climate change data

The research took place just before Australia’s 2019 federal election.

We asked 252 people who were planning to vote for the Greens and 252 people who were planning to vote for One Nation to consider some data we’d put together. To understand that data, they would need to do some mental maths, just like you would when looking at a typical scientific report.

Read Also: Global Inequality Is 25% Higher Than It Would Have Been in a Climate-Stable World

While there was no significant difference in the mathematical ability between the two groups of voters overall, it seemed that political affiliations can have an impact on how people answered a mathematical question, depending on the subject.

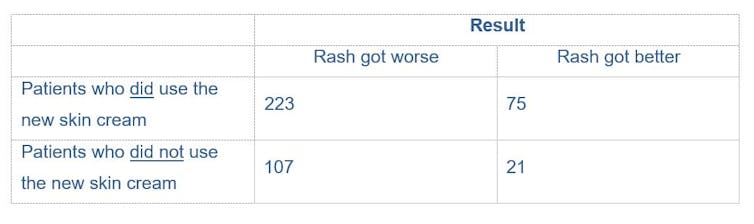

For example, in one experiment we told participants that data in the scientific report was about whether a new skin cream would cure a rash, as shown below.

We asked them to indicate whether the experiment shows that using the new cream is more likely to make the skin condition better or worse. Participants in our study got the correct mathematical answer 48% of the time.

However, when we showed them exactly the same data but said it was about whether closing coal-fired power stations would significantly reduce carbon dioxide emissions in the local area (by 30% or more), we got a very different set of answers.

For example, when the report showed CO₂ emissions would go down significantly, only 27% of One Nation supporters got the right answer.

When the report showed CO₂ emissions would not significantly go down, only 37% of Greens voters got it right.

So it seems our participants were less likely to answer a question correctly when it went against their political ideology.

Read more:

Climate sceptic or climate denier? It’s not that simple and here’s why

Spilt people according to maths ability

But what follows is really the interesting bit.

We decided to find out whether numeracy – maths ability – played a role in people getting the wrong answers. First, we looked at those with below-average numeracy.

We found many of these people just gave their preferred, ideologically aligned answers when it came to the climate change data question. This is a well-known effect called motivated reasoning.

But surely the more numerate groups of people, those better at maths, would fare better? Well, not really.

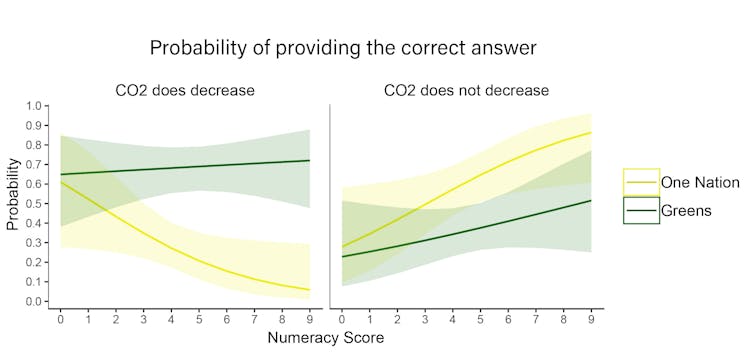

The groups of people with above-average numeracy sometimes did worse than the less numerate groups. Some did no better than chance at 50%, and some did far, far worse than that, as the graph below shows.

Matt Nurse, Author provided

When we showed people reports about CO₂ emissions, the more numerate people were much more politically polarized than any other group. For example, the participants considered a report showing that CO₂ would go down significantly, a One Nation supporter with a numeracy score of seven (out of nine) was only 5% as likely to provide the correct answer as a Greens supporter in the same numeracy category.

Motivations change brain function

This is counterintuitive, but this isn’t the first study to reveal this effect.

These findings build on research previously done by a Yale professor, Dan Kahan. The phenomenon is a type of motivated reasoning called motivated numeracy.

While Kahan’s previous research focused on the politically polarizing issue of gun control in the United States, some people suggested the same thing might happen with other topics, particularly climate change.

Read more:

Guns, politics and policy: what can we learn from Al Jazeera’s undercover NRA sting?

Our research is the first to confirm this.

These findings build on the theory that your desire to give an answer in line with your pre-existing beliefs on climate change can be stronger than your ability or desire to give the right answer.

In fact, more numerate people may be better at doing this because they are have more skills to rationalize their own beliefs in the face of contradictory evidence.

So what?

You might ask whether it really matters if people sometimes get the wrong answer on questions like this.

We’d argue yes, it does matter. Successful democracies rely on a majority of voters being able to identify and understand risks, and make the appropriate voting choices.

If people remain entrenched in their ideological corners when threats come along, and are unwilling to face facts, societal problems can fester, potentially becoming much more difficult to resolve later.

Just imagine scientists had discovered human activity was damaging our atmosphere. They said this problem would cause Earth’s climate to get hotter and threaten our livelihoods. Politicians and the people they represented saw this as a legitimate issue worth acting on, regardless of their political views. Imagine the world united to fix this problem, even though it would cost a lot of money.

In fact, we don’t need to imagine too much, as this isn’t just a hypothetical situation. It actually happened when scientists found evidence the use of industrial chemicals was depleting the ozone layer.

In 1987, for the first and only time, all 197 members of the United Nations agreed to sign the Montreal Protocol regulating the man-made chemicals that destroy the ozone layer. More than 30 years later we can measure the benefits of this agreement in our planet’s atmosphere.

A matter of science and climate change data, not politics

Unlike the current climate change debate, people largely saw this risk as a matter of science, not politics.

But it seems people are increasingly encouraged to see risks like this through a political frame. When this happens, facts can become irrelevant because no matter how smart people are, many will simply deny the evidence to protect their side of the political debate.

Read more:

Communicating climate change: Focus on the framing, not just the facts

Societies need to make good choices for their survival and those choices need to be based on facts, regardless of whether everyone likes them or not.

This research was conducted by Matthew Nurse as part of a master’s thesis at the Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science.

Will J Grant, Senior Lecturer, Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.