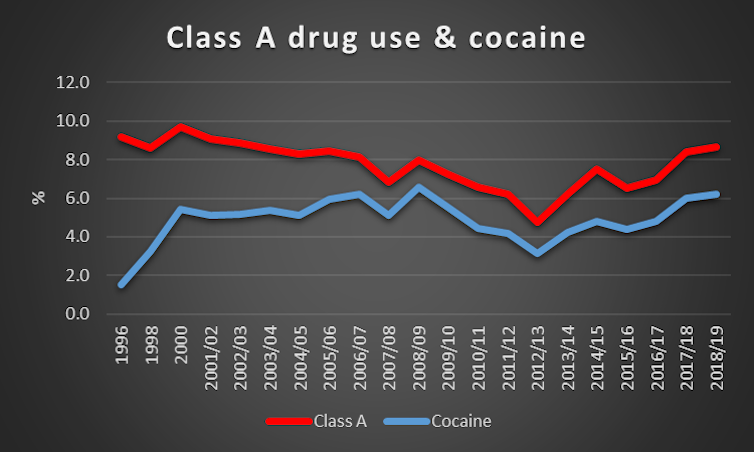

Once a year we get a glimpse of how many people are using drugs such as heroin and cocaine in England and Wales. The Home Office conducts an annual household survey that asks people if they have used drugs and, if they have, to provide some details about which drugs and how often they have consumed them. For the fourth year in a row, overall drug use has risen. An interesting fact on its own, but as always, the devil is in the detail.

Class A drugs including cocaine are proving to be popular, second only to cannabis in popularity. Nearly a million people now report using the drug. Fewer people report using opiates, such as heroin – but this is largely due to limitations of the survey which, as a household exercise, will not pick up certain groups, such as the homeless or other transient populations. Equally, the survey will not capture the experience of students – another important cohort.

Home Office

One of the most striking elements of the data is the ease with which people, especially young people, can obtain controlled drugs. In 2018-19, almost 19% of respondents to the survey reported that it was “very easy” to get drugs within 24 hours. This a significant increase on the previous year’s figure of 14.5%.

Like ordering pizza

More than half of all young people, aged 16-24 years, said they could get drugs within 24 hours. This increased access to the drugs market could be as a result of more online availability through the dark web. Equally, the drugs market has developed in the way other legal markets have in the 21st century. Drugs can now be delivered straight to your door, often faster than pizza and there have been reports that suppliers are offering loyalty cards to customers.

Class A drugs such as cocaine carry the most severe penalties under current drug laws, so why are an increasing number of people willing to break the law? Perhaps recent high-profile political confessions of drug use have added to people’s perception that it’s acceptable – or at least not as frowned upon – to use drugs.

The Adaptive/Shutterstock

A recent YouGov poll suggests that most people think the current drug laws are ineffective in deterring drug use. And they would be right. The Home Office’s own evidence shows that tough law enforcement does not deter drug use, and the drug laws certainly did not deter any of those high-profile politicians from using cannabis or cocaine.

Despite changes in attitudes to drug use, government policy towards drugs has remained the same for half a century, so it’s hardly the evidence-based legislation it should be.

We can reduce drug use harm

Current policy approaches drug use as a criminal matter when all the evidence points to the need for a health and education-based approach. Most people will use drugs for pleasure and not come to any harm – but some will. The difficulty is predicting – prior to exposure – who is at risk, something that we are still struggling to get data on. Until then we need to think about how we can reduce the potential for harm that drugs pose to some people.

This is where we do have some evidence that we can use to reduce harm, but it is based on facilitating the safe use of drugs rather than trying to prevent drug use. Despite the public polling suggesting most people think current drug laws are ineffective, it is less clear what they would be willing to support.

It’s easy to say you support change, but would you be willing to see a drug consumption facility open up in your neighborhood or see your taxes used to increase specialist drug treatment? Yet these are just two ways that we know could halt the record numbers dying because of drug use. With 11 people a day dying as a result of drugs, this matters more than ever.![]()

Ian Hamilton, Associate Professor, University of York and Niamh Eastwood, Associate Member of the Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Middlesex University, Middlesex University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.