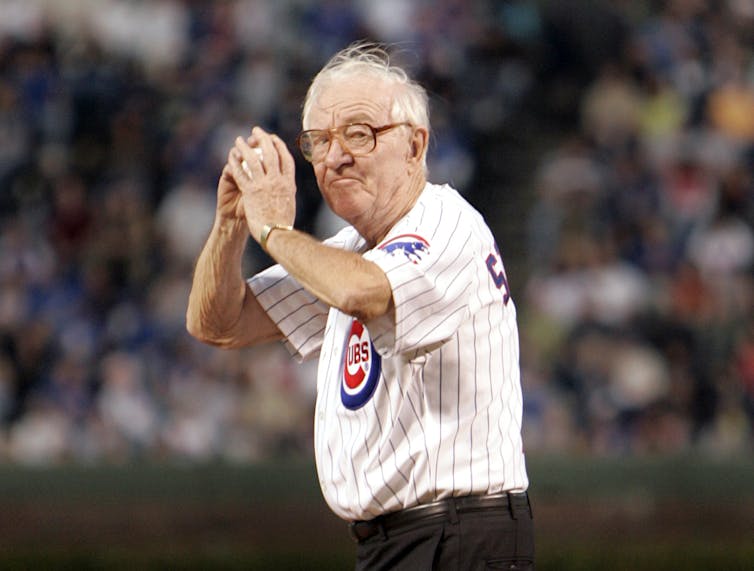

Babe Ruth’s famous, and controversial, “called shot” home run during Game 3 of the 1932 World Series between the New York Yankees and the Chicago Cubs

AP Photo/Jeff Roberson

Merritt McAlister, University of Florida

When I saw Justice John Paul Stevens this May at a gathering of his former law clerks to celebrate his 99th birthday, we discussed what he told me was the “easiest” assignment he ever gave a law clerk. I told him it was the best.

I clerked for Justice Stevens from 2009 to 2010, which was his final year on the Supreme Court. The court had some big cases that year, including Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the campaign finance decision that transformed the relationship between money and politics.

Read Also: What’s really behind baseball’s home run surge?

But the assignment we were talking about involved baseball and the Yankees. And the reliability of eyewitness testimony.

Justice Stevens was an unassuming legal giant. He was also one of the only living witnesses to Babe Ruth’s famous, and controversial, “called shot” home run during Game 3 of the 1932 World Series between the New York Yankees and the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field in Chicago. A 12-year-old John Stevens had attended the game with his father.

Stamptastic/Shutterstock.com

Over the years, the justice spoke vividly of the memory, describing how Ruth pointed to the center field scoreboard with his bat during the fifth inning and then hit a towering home run in that direction on the next Yankees pitch.

When he told the story at a judicial conference shortly before my clerkship began, an audience member, a judge, approached Justice Stevens privately to question his memory.

That judge’s father had also been at the historic game. His father had described with equal clarity how Ruth’s “called shot” home run had landed in the bleachers next to where he was sitting and nowhere near the center field scoreboard, as Stevens had remembered. The justice had not seen the called shot after all, he said.

As was characteristic, Justice Stevens turned the story into a charming anecdote about the reliability of eyewitness testimony. In 2010, at age 89, he told The New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin that it was a cautionary tale about trusting the memory of an “elderly witness.” (His words, not mine.)

After Toobin’s article came out, it occurred to the justice that maybe both he and the judge’s father had been right. Maybe there had been two home runs that day. Maybe the judge’s father had seen another home run, while the justice had seen the actual called Yankees shot.

A scorecard from the game that hung in the justice’s chambers confirmed that Ruth had, indeed, hit two home runs, but we didn’t know where each had landed.

I was given the plum truth-seeking assignment. A baseball fan myself, I eagerly searched through archives, with the help of the Supreme Court’s excellent librarians, to find out where the ball had landed on those two home runs.

We found confirmation that Justice Stevens had been right in The New York Times. The other judge’s father also had been right about seeing a home run that day – just not the called shot.

One home run, Ruth’s first, went where the judge had described. The second, the called shot, had gone where the justice remembered – near the center field scoreboard.

When I reported my findings, Justice Stevens was gleeful. In that moment, I saw both the 90-year-old justice that his law clerks loved and deeply admired and also the 12-year-old boy who had witnessed perhaps the greatest home run in the history of baseball.

Justice Stevens was open to being wrong, even though it was a memory he had held to firmly for decades. He knew as well as anyone that eyewitness accounts were unreliable and that memories fade and change over time. But he still sought the truth; he wanted the facts.

Not everyone agrees about the significance of Ruth’s gesture before he hit the shot to center field, but the home run’s trajectory, at least, was settled with reliable evidence. Justice Stevens couldn’t have been happier.![]()

Merritt McAlister, Assistant Professor of Law, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.