The dark skies of the great outdoors help people to see the wonders of space, either with the naked eye or using telescopes. That’s why observatories are usually placed in high altitudes or remote locations, where there’s often outstanding natural beauty and little light pollution.

A report commissioned by the UK government recommended that every school child should be given the opportunity to spend a night under the stars in such places.

In my research I’ve noticed the awe and wonder that young people feel while watching the stars in dark sky sites such as the stone circle at Callanish in Scotland. The stones here are made from Lewisian Gneiss – the oldest rock in Britain – formed three billion years ago and erected by people more than 5,000 years ago. Here, the immensity of time and our universe can be felt in every fibre of the body.

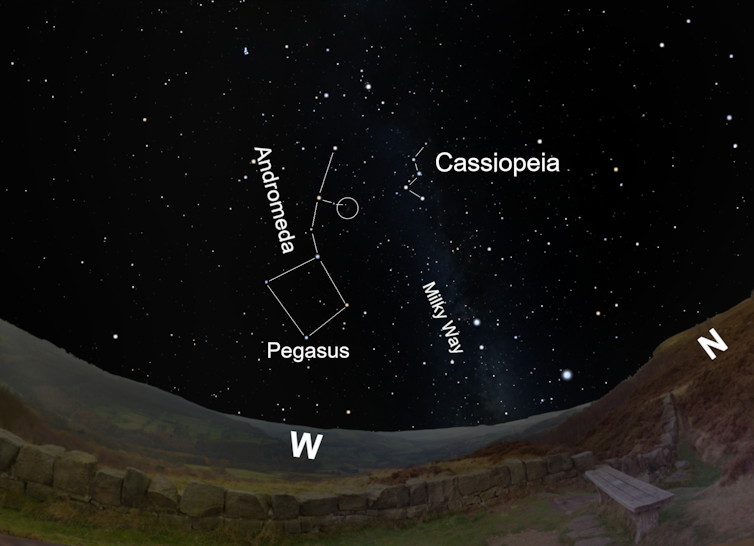

Exploring the night sky in a national park could be a transformative experience for both young and old. They might see the dust lanes of the Milky Way galaxy for the first time, stretching across the night sky. Learning that this band is made from millions of stars, each not too different to our sun, gives us a new appreciation of the universe and our place within it.

Perhaps they might spot the closest galaxy to ours – Andromeda, 2.5m light years away – and marvel at how the light they’re seeing set off just before our species walked the Earth.

Daniel Brown/Stellarium, Author provided

The stars at home

But protecting dark sky sites in national parks is only half the story. It’s a shame that light pollution means these wonderful experiences are only possible far from home. Connecting everyone with the wonders of the universe should be taken up where people live.

In the UK the Dark Sky Discovery partnership – a network of astronomy and environmental groups – has developed dark sky discovery sites that offer safe and accessible stargazing in towns and cities. Urban parks are often perfect for this if the lighting can be reduced and shielded.

Outside of these sites, there are many things that stargazers can do to see more of the night sky close to home, like picking somewhere away from direct street light or switching off outdoor security lights. Turning off all the lights in the house can make a big difference to how much of the night sky is visible from outside.

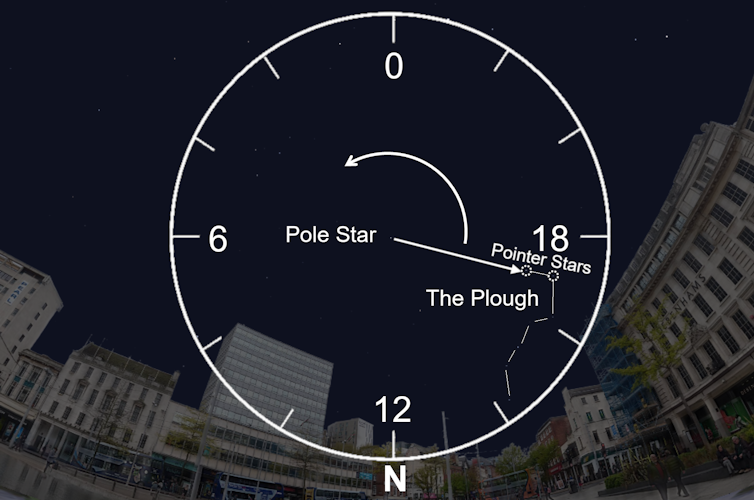

Daniel Brown, Author provided

The brightest objects in the solar system, such as Jupiter, Saturn, Venus and the moon, are still visible in cities. But these simple steps to limit light pollution near your home can make it possible to see more stars and even some of the brightest constellations. It’s possible to spot and track these objects from night to night and understand the pattern of their movements.

Noticing how the moon seemingly changes shape and color while rising, setting and moving through the surrounding stars from night to night is a memorable experience. The regular crazes around super moons suggest that people have sadly forgotten the nightly pleasure of tracking the moon.

Daniel Brown

It’s still nearly always possible to find the Plough on a clear night in the northern hemisphere. The two stars at its back – opposite the handle and known as the pointer stars – can also help people locate the pole star, which gives the direction of north. But, it’s interesting to remember that this is only a coincidence. Over thousands of years the Earth’s axis tumbles and points to many different stars that become, in each of their era, the new pole star.

You can even tell the time using the position of the pointer stars in the Plough, as if the whole constellation were a giant clock with the pole star at the center.

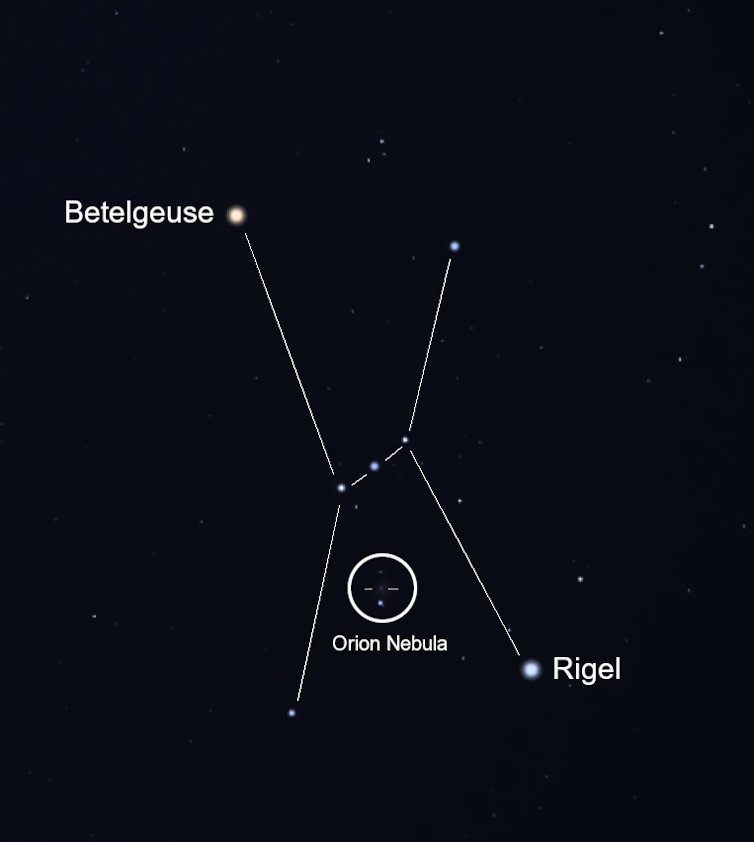

Spotting Orion is also simple enough when looking for his belt – three bright stars in a line. Looking below the belt reveals three much fainter stars forming the sword. The object at the middle of this is not a star, but the Orion Nebula – a cosmic nursery of new stars.

Daniel Brown/Stellarium

Local action on light pollution – by people in their homes or local councils dimming and reducing non-essential lighting in parks – might seem small in scale, but the results can be impressive.

While dark sky sites remind us of how beautiful the night sky is, bringing that opportunity back to where most people live could broaden the appeal of stargazing to those who’ve never tried it before. School trips to these places are still a wonderful idea, but allowing children and their families to experience the majesty of space in their own neighborhood could connect them to the stars for life.![]()

Daniel Brown, Lecturer in Astronomy, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.