If you thought 76-year-old Robert De Niro and 79-year-old Al Pacino were done starring in blockbuster gangster films, think again.

Both assume lead roles in Martin Scorsese’s “The Irishman,” which chronicles the life of hitman Frank Sheeran and labor union leader Jimmy Hoffa over several decades.

Different actors weren’t cast to play the younger versions of Sheeran and Hoffa. Instead, Scorsese and his production team utilized “de-aging” technology to make De Niro and Pacino appear younger.

To de-age actors, a visual effects team creates a computer-generated, younger version of an actor’s face and then replaces the actor’s real face with the synthetic, animated version.

Human beings are actually quite good at picking up on even the smallest of details of the human face. For this reason, we had several project lines devoted to advancing these types of digital human technologies at Disney Research, where I spent nearly a decade of my career.

Animators need to avoid what’s called “the uncanny valley” – a pitfall in realistic, computer-generated animation that animators have been struggling to overcome for decades.

Into the uncanny valley

In 2010, I was a contributing author to a paper titled “The Saliency of Anomalies in Animated Human Characters.”

In the paper, we found that audiences are much more sensitive to distortions in computer-generated faces, even when larger, seemingly more obvious distortions are present on the body. In other words, there’s more room for error when creating computer-generated bodies and a much smaller margin for error when creating computer-generated faces.

This brings us to the uncanny valley. The term refers to the uncomfortable feeling viewers might experience when they see computer-generated faces that “aren’t quite right.”

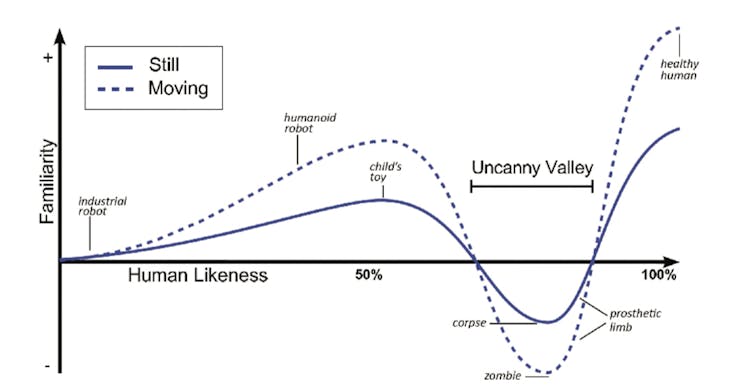

The term was coined in 1970 by robotics professor Masahiro Mori. Mori hypothesized that as a humanoid becomes more lifelike, an audience’s “familiarity” toward it increases until a point where the humanoid is almost lifelike, but not perfectly lifelike. At this point, subtle imperfections lead to responses of repulsion or rejection.

The term “uncanny valley” comes from visualizing this idea on two axes.

J. Hodgins et al., Author provided

The x-axis describes “human likeness” or realism, while the y-axis describes “familiarity,” empathy or emotional engagement. The steep falloff in the graph represents the uncanny valley – the point at which people recoil and feel less empathy. The effect is stronger if the humanoid is moving.

Read also: Game of Thrones: teasing hints from Welsh language and legends have been hiding in plain sight

Animating appealing people

While the hypothesis originated in the robotics community, the concept of the uncanny valley gained popularity in the animation industry. For animators, the word “appeal” may be the closest relative we have to Mori’s familiarity.

Appeal is one of the 12 basic principles of animation that animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston outline in their book, “The Illusion of Life.”

In animation, appeal has to do with the character’s magnetism – whether he or she is beautiful, cuddly and kind, or ugly, disgusting and mean. Animated human characters, like Elsa in “Frozen,” tend to be stylized in a way that caricature human features, which allows us to caricature their motion as well.

Two computer-animated films from 2004, “The Polar Express” and “The Incredibles,” highlight this quandary.

“The Incredibles” was the first Pixar film that starred actual human beings instead of toys, bugs, fish or monsters. But the animation team didn’t try to make them look like real humans: They had larger eyes, soft, rounded silhouettes and simplified features. These types of design decisions work toward the “magnetism” of a character that most audiences ultimately find appealing.

“The Polar Express,” on the other hand, used performance capture technology so Tom Hanks could play five lifelike characters, including the 9-year-old protagonist.

Mapping a 50-year-old’s facial movements onto a 9-year-old boy’s face ended up creating a whole host of problems. For example, how should a moment where Hanks is bursting with excitement be transferred to a 9-year-old’s face? In order to use performance capture data to transplant an actor’s expressions onto an animated character, animators need to do what’s called “motion retargeting.” Because this was new territory for animators – and due to the technological limitations of the time – the nuanced facial expressions that make Hanks a talented actor were lost.

In retrospect, this is a fairly extreme example of de-aging – and one that didn’t sit well with most viewers.

The animated boy seemed “off,” with audiences and critics disturbed by what Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers described as the film’s “spooky” and “lifeless” animation.

Adapting to the animation technology

Not all trips into the uncanny valley end up fruitless. Animators can learn from experience.

For example, in 1988, Pixar released the short film “Tin Toy,” in which an animated baby torments a group of toys. At the time, Pixar hadn’t developed the technology needed to depict appealing humanoid characters. The baby almost evokes Chuckie from the horror film “Child’s Play.”

The film’s shiny plastic and metal toys, on the other hand, worked well within the constraints of the era’s computer animation technology. This is largely why the ensuing “Toy Story” franchise ended up featuring toys, not humans, as the protagonists.

It also helps to apply performance capture technology on computer-generated characters who aren’t fully human. That’s what James Cameron did in his 2009 blockbuster, “Avatar.”

The film’s Na’vi species are humanlike but remain an alien species. They’re blue. They have large, radiant eyes. The bridge of their nose is wide and stiff, while the tip of their nose is catlike.

Importantly, however, the animated characters of the film still look somewhat like the actors who played them. Sigourney Weaver’s avatar looks very much like Sigourney Weaver, which helps avoid the “retargeting” problem that occurred in “Polar Express.” Audiences don’t expect the alien race to look or move exactly like humans.

Surmounting the animation valley

While the technology continues to improve, recreating realistic human faces remains one of the most difficult tasks for animators.

A strong example of de-aging technology can be seen in “Blade Runner: 2049.” The shot of a de-aged Sean Young is a stunning technical feat, but the scene also doesn’t ask too much of the computer-generated performance. In fact, the computer-generated version of Young only says a couple of sentences. Most of all, the use of the technology actually serves the story. The moment is designed to be eerie; audiences are supposed to be unsettled.

Because “The Irishman” is based on a real story, with realistic characters with realistic faces, audiences are much more sensitive to the use of de-aging technologies.

My guess is that some viewers won’t notice the technology, some will marvel at it and others will find it distracting. I usually fall into the latter two categories. It is incredibly distracting to me despite the impressive quality of the de-aging.

I often teach my students that when working with new technology, just because we can, that doesn’t always mean we should.

Interestingly, De Niro won his first Academy Award for his portrayal of a young Vito Corleone in “The Godfather: Part II,” while Marlon Brando played the older Vito Corleone.

If Francis Ford Coppola had today’s technology and could have simply “de-aged” Brando, would he have done so? And how would that have changed one of the most memorable gangster films of all time?

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

Moshe Mahler, Special Faculty, Carnegie Mellon University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.