Without question, the final movement of the Ninth Symphony contains one of the most famous tunes ever written by Beethoven. Since its first performance in 1824, the “Ode to Joy” has been repurposed in endless ways, both reverential and exploitative, from performances at the Berlin Wall to its use in tawdry advertising.

This final movement, which combines voices and orchestra, is based on Friedrich Schiller’s 1786 poem extolling a humanist theme of universal joy. Beethoven started sketching ideas for a musical setting of the text in his late 20s, and, given an initial admiration for Napoleon, he was likely attracted to the poem’s revolutionary undertones.

Read more:

Decoding the music masterpieces: Bach’s Six Solo Cello Suites

‘Obstreperous roarings’

Yet the Ninth Symphony is not a work from Beethoven’s rebellious youth. Rather, it is a “late” work. Premiering 12 years after his Seventh and Eighth Symphonies (and three years before his death), it followed a period in which he appears to have struggled with life. His output had dropped, certain works were of dubious merit, and he had endured a humiliating legal wrangle to gain custody of his nephew. In short, he suspected his time as Vienna’s most popular composer had ended.

So, why did Beethoven choose to set this text? Is it an expression of decisive optimism, a sign of deeper reconciliation, or an attempt to convey a message which would otherwise fail through music alone?

Given the powerful questions the final movement of this symphony poses, and the enduring popularity of the famous tune, it is paradoxical that Beethoven thought he had made a mistake.

Read also: Ancient Greek music: now we finally know what it sounded like

Following its first performance, he briefly canvassed plans for an instrumental replacement for the Ode to Joy. The symphonic form, as it was then understood, was not only purely instrumental but had also come to signify elemental purity. Arguably, it was a class of music that should rise above matters expressible merely in words.

Yet perhaps a bigger “mistake” was yet to be recognised. In the late days of the so-called “classical” period, a symphony was typically around 30 minutes long. However Beethoven challenged audiences to remain attentive here for over an hour. Similarly, orchestras were not yet as accomplished as later professional ensembles, and the taxing writing for wind and brass players – not to mention the stratospheric vocal lines – were beyond the scope of many.

Scott Davie

Despite its commission by the London Philharmonic Society (for a fee of £50), the first performance occurred in Vienna on 7 May, 1824. It followed a petition insisting that the city be the first to hear the new work, circulated by notable supporters. Even with many fans in attendance, however, some negative views were privately expressed.

Read more:

Decoding the music masterpieces: Shostakovich’s Babi Yar

In London the following year, the Ninth Symphony was greeted by a hostile and conservative press, who suspected the composer’s deafness and old age had led him astray. Influential London music publication the Harmonicon described the performance as a “fearful period indeed”, which put “the patience of the audience to a severe trial”.

While that reviewer believed the work could be saved through massive cuts, the Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review was entirely dismissive, carping about the “obstreperous roarings of modern frenzy” in art.

More than a Beethoven finale

Within a decade, however, views about the symphony began to change. Professional orchestras and dedicated conductors – such as Mendelssohn, Berlioz and Wagner – brought order to performances, its substantial length became less remarkable, and it became a universal favourite. Yet the Ninth Symphony, which comprises of four varied movements, is about more than its culminating finale.

The opening of the symphony is famous for the way its powerful principal theme emerges, as if from nebulous obscurity.

When this theme later returns, fury is unleashed, with pitches given to the lower instruments of the orchestra fundamentally clashing with the overall tonality of the movement.

As was typical in Beethoven’s music, the closing coda section of the first movement is long, accounting for almost a quarter of its length. One passage has been thought to resemble a funeral march.

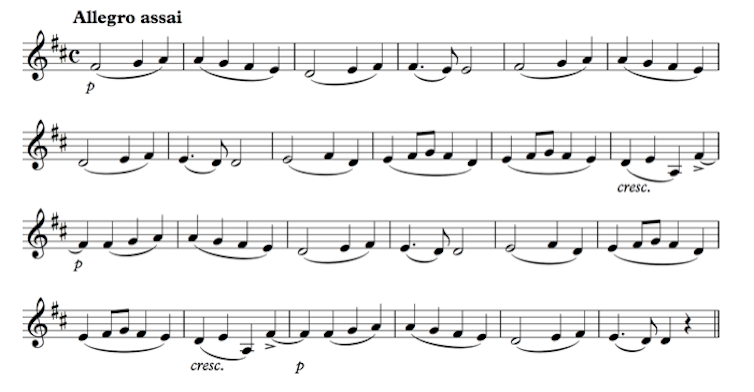

A slow movement would normally follow in a traditional symphony, but Beethoven instead provides us with the humorous Scherzo (literally meaning “joke” in Italian). At first, the broader beats appear to be counted in groups of four…

…yet as the movement progresses Beethoven plays a little trick, and the beats now appear in vigorous “threes”.

The slow movement that follows takes the form of “double variations”, where two musical themes interplay in constantly varied form. In it, Beethoven provides a “tease” of one of the tonal shifts that will underpin a significant and revelatory moment in the final movement.

The structure of the final movement is unique, to the extent that a satisfactory analysis still eludes scholarly consensus. It begins with a powerful dissonance (which Wagner described as a “horror fanfare”), which leads to a kind of double introduction, played first by the orchestra and then with chorus.

The baritone singer’s solo, on lines written by the composer, provides the reason for this, his statement “O Friends, not these tones!” appearing to comment on the reprise of earlier themes just presented by the orchestra.

Subsequently, the “joy” theme is shared among the chorus and soloists, its treatment increasingly varied. Perhaps the most surprising variation is given a Turkish styling, the percussion instruments reminiscent of an Ottoman military band.

Some have contended that this slightly farcical music is an ironic comment on the text’s earnest celebration of joy. What, then, might the non-pious Beethoven have had in mind when setting the words “Beyond the stars he surely must dwell”, words that evoke the deity?

It is a moment of radiant timelessness, but is it a statement or a question? The starry skies of a loving Father or, as music scholar Nicholas Cook has pondered, a reflection on “cosmic emptiness”?

As with Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis – the magnificent large-scale work that preceded the Ninth Symphony – a comparison of the text and how the music frames it can reveal glimpses of the composer’s human face. Yet what is perhaps greatest about music (and this music in particular) is the sublimely “unprovable” nature of the medium.

In one sense, this is just another symphony. At the same time, however, Beethoven has created an entity, one that continues to develop in context and meaning as future generations discover it.

Whatever message it encloses – whatever the poem’s “this kiss for the entire world” might mean – it advances always further from its creator, while never losing its ineffable truth.

Are you a music academic with an idea for a music masterpiece? Please get in touch.

Scott Davie, Piano tutor and Lecturer, Sydney Conservatorium Music, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.