While recording with Miles Davis, Columbia Records jazz producer Teo Macero sent a memo to the label’s executives that read simply:

Miles just called and said that he wants this album to be titled: Bitches Brew. Please advise.

The uneasy terseness of that brief statement encapsulates the tension in Davis’s career that lay behind the recording. The trumpeter had a prickly reputation and although they would develop a successful working relationship, he had got off to a shaky start with new label president Clive Davis in a clash over his royalty agreement.

It also reflects the balance between chaos and precision, past and present, in the album itself – released 50 years ago – that helped to redefine jazz and had an enormous impact on popular music at large.

Read Also: The Wall cemented Pink Floyd’s fame but destroyed the band

Not many artists in any medium get to recalibrate their field. Fewer still do so more than once. Davis, by the end of the 1960s, had already been at the forefront of key developments in jazz. After early years under the auspices of be-bop revolutionaries including Charlie Parker, his own stylistic development pulled the music in his wake, with the “cool jazz” of the 1950s, and then the innovation of “modal jazz” exemplified by the hugely successful Kind of Blue.

While his landmark quintets had helped to nurture the careers of giants like John Coltrane, Davis remained unsatisfied, commercially and artistically. Always musically restless – and always with an eye on the box office – he was acutely aware that rock had changed the commercial landscape and, typically, alive to the aesthetic potential for jazz. He described the situation in his autobiography:

Nineteen sixty-nine was the year rock and funk were selling like hotcakes and all this was put on display at Woodstock. There were over 400,000 people at the concert… And jazz music seemed to be withering on the vine.

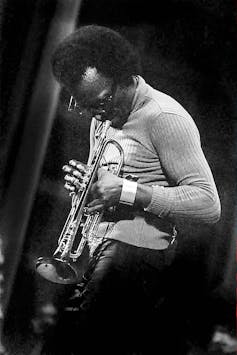

Virtuoso vision of Miles Davis

Inspired by the funk of Sly and the Family Stone, and the psychedelically infused blues of Jimi Hendrix, Davis accelerated the use of electric instruments he had already pioneered on, Filles de Killmanjaro and In A Silent Way.

A key influence was his then partner, Betty – who had her own recording career). She introduced Davis to psychedelia and Hendrix, and inspired the album’s title, noting that “there was nothing derogatory about it” (not a foregone conclusion, given Davis’s relationship history).

The album also pioneered jazz compositional practice. Rather than entering the studio with scores, Davis gave his band sketches, scribbled chord sequences, and proceeded, in his own words, to “direct, like a conductor”. The music thus evolved organically across the sessions, driven by the musicians’ individual virtuosity, corralled by the force of Davis’s vision.

The dense, brooding sound was also a factor of the decision to use multiple players on most tracks: three keyboards, two bassists, two drummers – a cast comprised of future leaders, including saxophonist Wayne Shorter, guitarist John McClaughlin, drummer Jack DeJohnette, keyboardists Chick Corea and Joe Zawinul.

Birth of fusion with Miles Davis

While the co-mingling of jazz improvisation with rock instrumentation had roots in Davis’s work leading up to Bitches Brew, its explosive – and initially divisive – release made dialogue between the two forms inescapable. McLaughlin, Corea and – in their band Weather Report – Zawinul and Shorter would all become leading lights of what came to be known as “fusion”.

JPRoche via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

The use of the studio was central to the innovation at play. Davis instructed Macero to “just let the tapes run and get everything we played… Just stay in the booth and worry about getting the down the sound”. Davis and his band created layered textures of sound, bringing in rock distortion, funk and Latin rhythms to create a melange that hadn’t been heard before in either jazz or rock.

Macero’s editorial role shaped the hours of jamming, bringing focus to the project, moving, cutting and splicing the raw materials, making the studio itself the final ingredient and adding punch to the sprawling improvisations.

Black Power and politics

From the title to the music itself and the distinctive cover art, the album also acknowledged the surrounding political situation of the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, and black consciousness in America. Its dissonance was as much a response to the burgeoning Black Power movement as an appeal to the white rock audience. The tautness in the music derived from Davis trying to combine these variegated strands in both a product and a reflection of the turbulent times.

Its refusal to resolve these into an easily digestible form was ultimately what made it a lynchpin of progress for jazz. It sold half a million copies by 1976 (compared to Davis’s usual sales of around 60,000) and was his highest entry on the Billboard charts. Jazz and rock may have ultimately pursued different trajectories. But the longer-term influence of Bitches Brew stretched far beyond its home genre, with the likes of Radiohead citing the precarious mixture of precision and collapse as an inspiration.

The 20th century contained many icons who reinvented themselves multiple times. Davis’s signal achievement was to remain consistent in his search for new sounds, reshaping the musical world around him each time. Bitches Brew reinvigorated jazz as a commercial and artistic force, propelling fusion into the musical bloodstream of the 1970s.

It launched the next generation of jazz leaders from what previous alumnus – saxophonist Jackie Mclean – had called “the university of Miles Davis”, uncovering new paths for rock and studio practitioners of all stripes as it did so.![]()

Adam Behr, Lecturer in Popular and Contemporary Music, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.