Elton John, Adele and R.E.M. did it. So did Rihanna and the Rolling Stones. If Donald Trump tried to use her music, Taylor Swift would likely do it, too. Many musicians have said “no” when politicians try using their music for campaigning. But Bruce Springsteen may be the most famous naysayer of all.

In September 1984, Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” was atop the charts, and Ronald Reagan, running for reelection against Walter Mondale, told a New Jersey audience that he and the singer-songwriter shared the same American dream.

Springsteen disagreed.

Three days later, performing in Pittsburgh, Springsteen spoke about his version of that dream.

“In the beginning, the idea was we all live here a little bit like a family where the strong can help the weak ones, the rich can help the poor ones. You know, the American dream,” he said in between songs.

“I don’t think it was that everybody was going to make a billion dollars but that everybody was going to have an opportunity and a chance to live a life with some decency and some dignity.”

June 4, 2024, marks the 40th anniversary of “Born in the U.S.A.,” Springsteen’s top-selling album. In my recent book, “Righting the American Dream: How the Media Mainstreamed Reagan’s Evangelical Vision,” I describe the president’s attempt to use Springsteen’s lyrics to support that vision, which included cutting welfare, boosting the military and ending abortion – all positions dear to the religious right.

Springsteen had a different vision, and Reagan’s attempt to co-opt it spurred the singer to be more explicitly political in his words and actions.

Blinded by the light

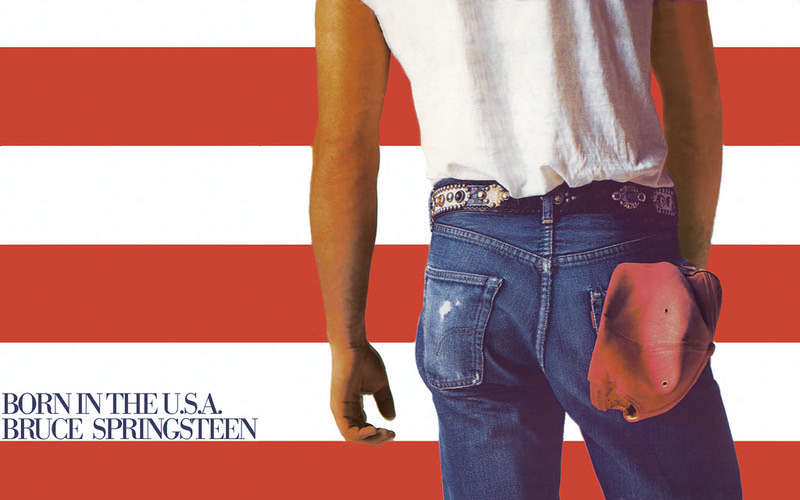

The confusion over “Born in the U.S.A.” is easy to understand. Just look at the album’s cover art.

Shot from the rear, Springsteen is facing a huge American flag. The flag’s red and white stripes, along with Springsteen’s white T-shirt, blue jeans and red baseball cap, all telegraph, “America.”

So why a butt shot of the blue-jeaned rocker whose pose screams youth, sex and swagger?

The photo is a Rorschach test, a purposeful mixed message.

Lawren/flickr, CC BY

Spingsteen called

the album’s eponymous title song “one of my greatest and most misunderstood pieces of music.” It’s driven by forceful, pummeling drums and a synthesizer’s haunting refrain. Springsteen’s gruff rasp can make it difficult to hear the lyrics, which express the anguish of a Vietnam vet who regrets enlisting and faces unemployment at home.

Yet the song’s chorus, which Springsteen sings proudly and loudly, fist in the air, repeats “Born in the U.S.A., I was born in the U.S.A.”

Springsteen was doing two things: criticizing the war and subsequent treatment of veterans and affirming his American birthright. The song was, in his words, “a demand for a ‘critical’ patriotic voice along with pride of birth.”

Bruce Springsteen, Human touch

But its message eluded many listeners, including conservative columnist George Will, whose wife had been given two tickets to a concert.

Afterward, Will told his Washington Post readers that Springsteen “is no whiner, and the recitation of closed factories and other problems always seems punctuated by a grand, cheerful affirmation: ‘Born in the U.S.A.!’”

Will, a favorite of the Reagan’s inner circle, was the likely source for the president’s mistaken view that he and Springsteen shared the same American dream.

Springsteen wrote about everyday people: bus drivers, factory workers, waitresses and cops. Reagan needed their votes, but not all of them were his people. His fiscal policies benefited wealthy Americans and corporations but did little for working families and the poor.

Springsteen said as much in a Rolling Stone interview at the end of 1984: “And you see the Reagan reelection ads on TV – you know: ‘It’s morning in America.’ And you say, well, it’s not morning in Pittsburgh. It’s not morning above 125th Street in New York. It’s midnight.”

In that same interview, Springsteen admitted that he last voted in 1972, when his candidate, George McGovern, lost to Republican incumbent Richard Nixon. His preference, he said, was “human politics” – concrete action with a direct effect on local communities.

He put that into practice at the Pittsburgh concert following Reagan’s shout-out. Making a US$10,000 donation to a food bank for unemployed steelworkers, he urged his audience to also support the cause. His pitches for local food banks have been a concert staple ever since.

The promised land

Reagan articulated his American dream in speeches and interviews.

He believed God had blessed America with freedom – a freedom embodied in free markets, limited government and the freedom to live according to your religious beliefs.

Springsteen has made his American dream the subject of his music: a nation that welcomes immigrants, condemns racism and opposes economic inequality. Its people stand together even – especially – amid tragedy.

Before Reagan cited him as a Republican muse, Springsteen was content to let his music convey his politics.

Afterward, he was more candid, often riffing on a favorite phrase, “Nobody wins, unless everybody wins.”

In 2004, he jumped into electoral politics, supporting John Kerry’s presidential bid. At a large Midwest rally, he warned that the ideals championed in his music were at risk, “‘United We Stand’ … and ‘one nation indivisible’ aren’t just slogans. They need to remain the guiding principles of our public life.”

Four years later, Springsteen campaigned for Barack Obama and again in 2012. He supported Hillary Clinton in 2016, and in 2020 he restyled “My Hometown” for a Biden campaign ad.

No surrender

In May 2024, things came full circle when Donald Trump, the putative GOP presidential candidate, name-checked Springsteen at a New Jersey rally. But this time, the candidate wasn’t praising the Garden State troubadour.

He called Springsteen a “wacko,” before claiming that the Boss and other “liberal singers” had nonetheless voted for him in 2020. Then Trump falsely added that his crowds outnumbered Springsteen’s.

But Springsteen made his opinion on the candidate clear in a 2020 interview, when Trump was running for reelection: “I don’t know if our democracy could stand another four years of his custodianship.”

Springsteen’s recent collection of R&B standards is titled “Only the Strong Survive,” and on the cover, the rocker is dressed in black, grizzled but game, looking directly at the viewer.

With the title, is he hinting that Reagan’s evangelical vision and Darwinian approach to economics had crushed Springsteen’s own American dream?

Or does his assured pose convey his belief that there’s still “treasure for the taking, for any hard working man, who’ll make his home in the American land”?

Diane Winston, Professor and Knight Center Chair in Media & Religion, USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.